End-Stage Respiratory Disease

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

End-Stage Respiratory Disease

According to World Health Organization, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is now the third leading cause of death globally, and chronic lower respiratory disease is the sixth leading cause of death in the U.S. (2022 Centers for Disease Control). Chronic respiratory diseases are comprised of conditions that affect the respiratory tract and lungs, and the burden on the economy is comparable to lung cancer. These respiratory conditions are both progressive and irreversible. We often think of COPD or lung cancer in isolation, but respiratory decline is also an end-stage sign with many predisposing factors and, fortunately, the symptoms are easily identified and treated with comfort medications.

Respiratory failure can be acute or chronic in nature. Physical signs of respiratory failure include dyspnea, nasal congestion, and/or cyanosis (blue skin, lips or nail beds). The most common types include hypoxemia (decreased oxygen in the blood) and hypercapnia failure (increased carbon dioxide in the blood). A simple pulse oximeter is helpful in monitoring blood oxygen levels on a daily basis. The chronic lung disease trajectory is similar to heart disease. The chronic lung disease trajectory is characterized by exacerbations, treatments (bronchodilators, antibiotics, steroids and/or oxygen), and recovery. While in contrast, the lung cancer trajectory is shorter with rapid deterioration. Both trajectories offer opportunities for symptom management and improvements in patients’ quality of life.

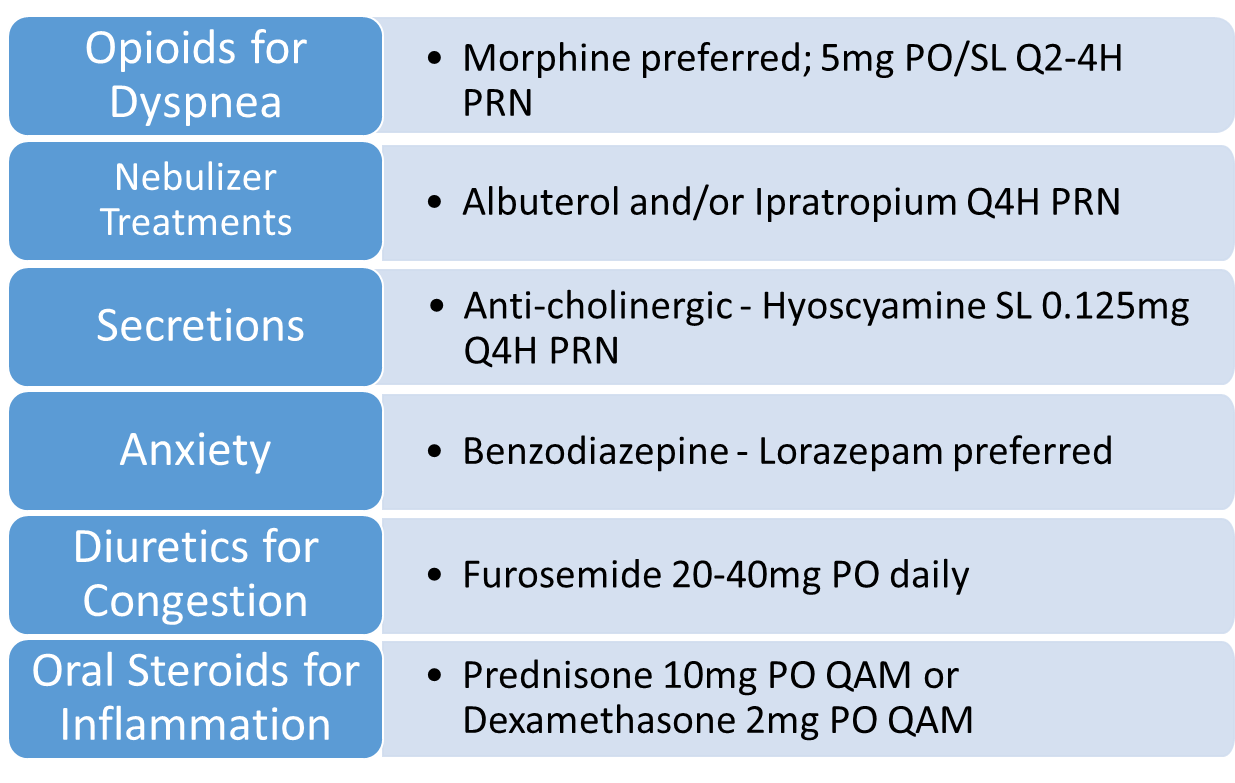

Chronic respiratory diseases include, but are not limited to, COPD, lung cancer, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, asthma, and pulmonary inflammation/infections. Below are the prevalent symptoms for end-stage lung disease patients, along with the standard medications to have available for comfort, when appropriate.

Sample Respiratory Toolkit

The COMFORT acronym lists several strategies to help manage acute shortness of breath (dyspnea) attacks:

C - Call for help

O - Observe and treat possible causes

M - Medicate with prescribed rescue medications

F - Fan directed at the face

O - Oxygen therapy, if indicated

R - Relaxation techniques, per patient preference

T - Timing; timely assessment of each intervention above

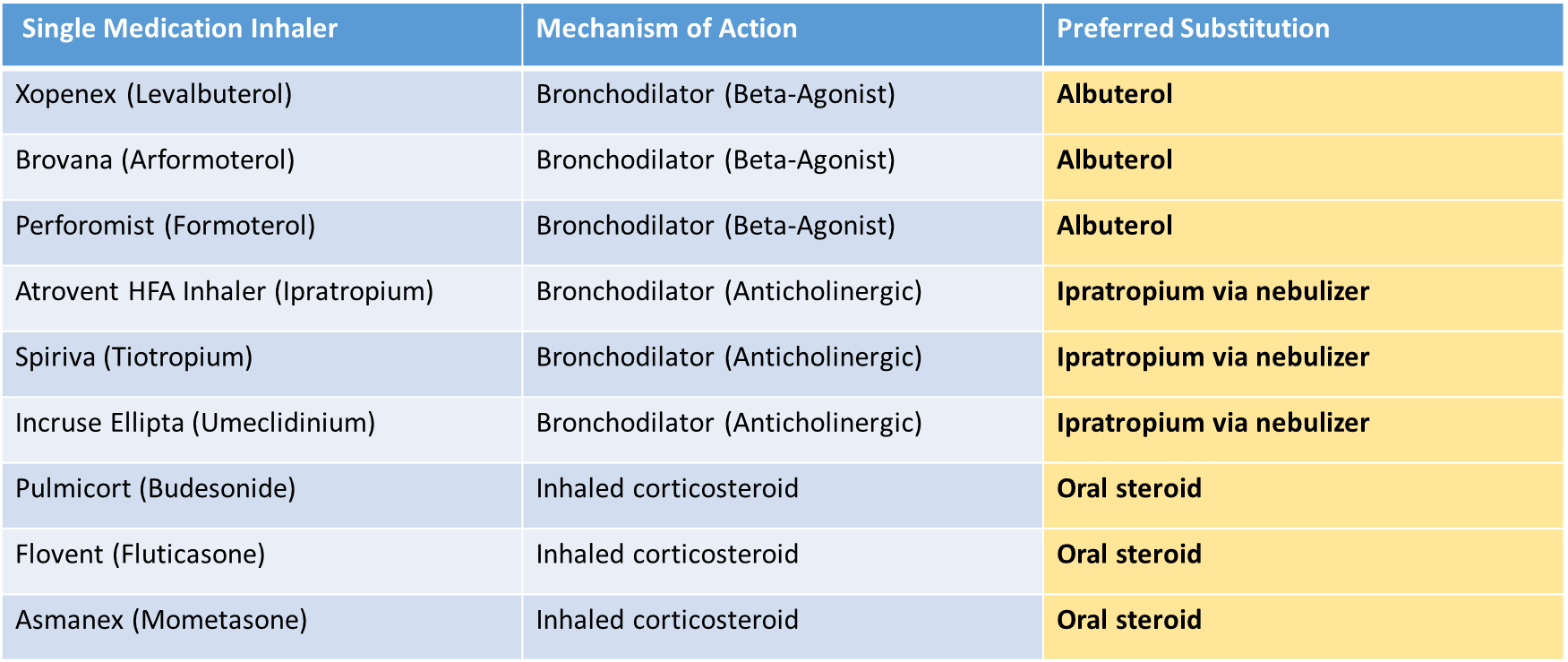

To optimize shortness of breath management as a patient declines, it’s often best practice to discontinue metered-dose and dry-powder inhalers that become too difficult to coordinate, and require manual dexterity and deep inhalation to achieve their desired results. Inhalers are designed to provide a thirty-day supply, which is often costly and makes the dosing difficult to titrate. When inhalers are not adequately helping with symptoms, additional medications can be added which leads to duplicate therapies and an increased risk for adverse effects.

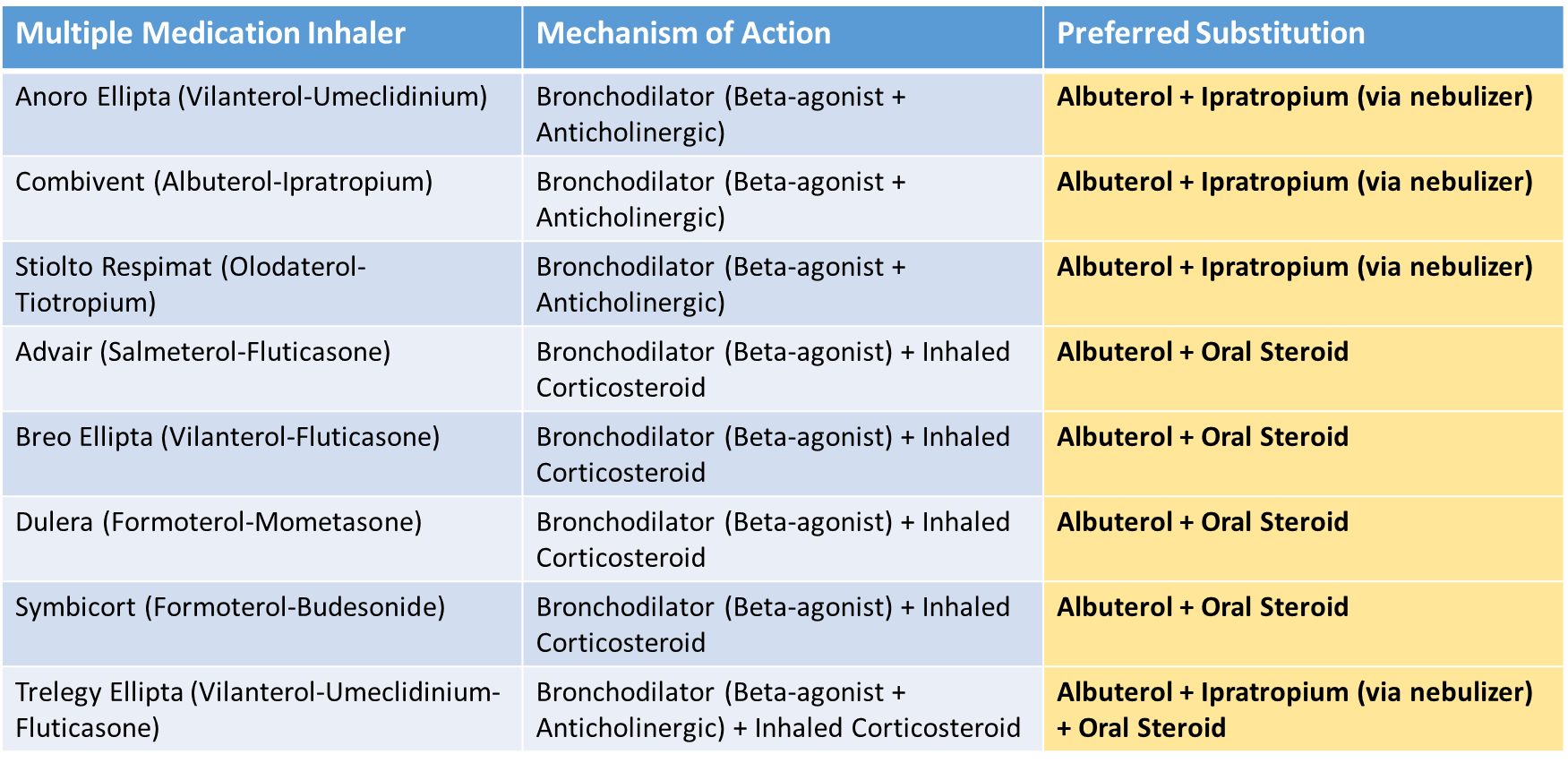

The preferred medication substitutions for these inhalers include the following:

- Albuterol, a short-acting beta2-adrenergic agonist (SABA) and Ipratropium, a short-acting anticholinergic (Antimuscarinic) agent

- Albuterol and ipratropium solutions for nebulization (individual or in combination) are the preferred commercially available formulations.

- Oral corticosteroids, which include: Prednisone or Dexamethasone (preferred with clinically significant fluid retention)

The below tables list single and multiple medication ingredient inhalers, their mechanisms of action and the preferred cost-effective and clinically-appropriate substitutions.

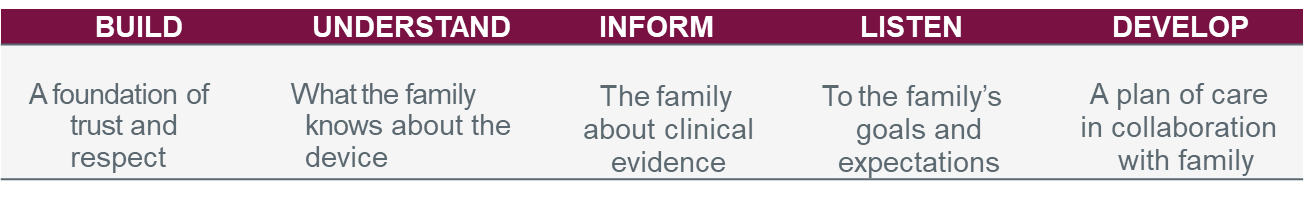

As hospice clinicians, we know all too well that it can be difficult to transition away from a medication or inhaler that has been helpful in the past. The BUILD Model provides a simple, yet effective framework for having important end-of-life conversations surrounding medication appropriateness and goals of care.

Below are a few helpful questions that can make this conversation a bit easier:

- “It seems you are having some difficulty using your inhalers. As your disease progresses it may be useful to make some adjustments to your medications. What worked before may not work as well for you now. Would you like to talk about making your medication routine a little less complicated?”

- “It sounds like it’s hard for you to make a decision about stopping your inhaler. Can I share what my experiences and observations have been?”

- Before I visit next week, I’ll give your doctor an update and get her input. She might suggest stopping the inhalers and using a nebulizer. Are you willing to give it a try?”

End-stage respiratory disease can be challenging to treat. It’s important to anticipate the patient’s symptoms and have your ‘toolkit’ in place. Meet the patient/family where they are, provide guidance and outline the potential

References

Jadhav U, Bhanushali J, Sindhu A, et al. (December 16, 2023) Navigating Compassion: A Comprehensive Review of Palliative Care in Respiratory Medicine. Cureus 15(12): e50613. DOI 10.7759/cureus.50613

Diseases & Conditions: Respiratory Failure. Cleveland Clinic. [Online] Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24835-respiratory-failure.

Bourke SJ and Peel ET. Palliative care of chronic progressive lung disease. Clinical Medicine 2014 Vol 14, No 1: 79-82.

De Oliverira EP and Medeiros PJ. Palliative care in pulmonary medicine. J Bras Pneumol. 2020;46(3):e20190280.

Gupta N, Garg R et al. Palliative Care for Patients with Nonmalignant Respiratory Disease. Indian J Palliat Care 2017;23:341-6.

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Deprescribing Toolkit Version 1.0. [Online} Available from: https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/NHPCO_Deprescribing_Toolkit.pdf.

Collier KS, Kimbrel JM, Protus BM. Medication appropriateness at end of life: a new tool for balancing medicine and communication for optimal outcomes--the BUILD model. Home Healthc Nurse 2013;31(9):518-524. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/homehealthcarenurseonline/Fulltext/2013/10000/Medication_Appropriateness_at_End_of_ Life A_New.10.aspx Accessed August 20, 2020.