Non-Traditional Symptom Management in Hospice and Palliative Care: Aromatherapy and Music

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

In hospice and palliative care, we sometimes need to consider complementary and alternative (CAM) therapies. One reason might be that the more “traditional” medication therapies are not effective, despite dose optimization, or a given patient has issues with drug allergies, interactions, and/or adverse effects. Or sometimes, patients and caregivers may desire complementary therapies. In a study that took place in a palliative IPU, 82% of the patients surveyed were interested in trying CAM therapies, with the greatest interest expressed in music therapy (61% of patients) and massage therapy (58% of patients). In this same study, 100% of “substitute decision makers” expressed an interest in having CAM therapies available for their loved ones to try.¹ Furthermore, aromatherapy and music therapy typically have a favorable benefit-to-risk ratio, although every patient is unique and should be evaluated individually.

Aromatherapy

When using aromatherapy oils, it is important to use high-quality, 100% pure and genuine essential oils from a reputable supplier or manufacturer that analyzes their oils. Aromatherapy products should typically be used in areas of good ventilation. Keep in mind that they are highly flammable – so they would not be safe or appropriate in patients who use oxygen therapy. Additional information on aromatherapy safety and basic principles can be found on the National Association for Holistic Aromatherapy website at www.naha.org.

One area of application for aromatherapy is nausea. An interesting study took place in an emergency department (ED), comparing inhalation of the fumes from topical antiseptic isopropyl alcohol (IPA) to oral ondansetron.² Patients who came into the ED with nausea were randomized into one of three interventions:

- IPA inhalation + ondansetron 4mg by mouth; OR

- IPA inhalation + placebo by mouth; OR

- Inhaled placebo + ondansetron 4mg by mouth

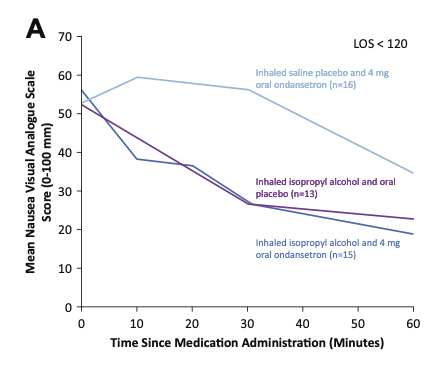

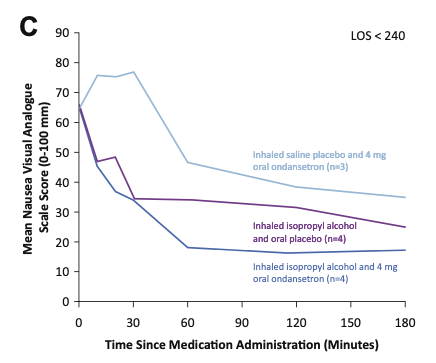

The patients reported their nausea scores using a 100mm visual analog scale at baseline and at 10, 20, 30, and 60 minutes after the intervention, and then every 60 minutes until ED disposition (i.e. admission to hospital or discharge home). They were allowed to take another inhalation at each measurement.

Patient results were grouped based on how long they stayed in the ED. Graph A shows results for patients in the ED less than 120 minutes. Up to the 30 minute mark, IPA inhalation groups (with or without oral ondansetron) saw significant improvement in their nausea scores. The group receiving oral ondansetron alone did not see any improvement within 30 minutes. After 30 minutes, those receiving oral ondansetron (with or without IPA) showed a greater drop in nausea scores than those receiving IPA inhalation alone.

Mean nausea VAS scores from study administration until ED disposition, for patients with ED disposition less than 120 minutes. From April MD, et al.

Graph C below shows results for patients in the ED less than 240 minutes. Results before the 30 minute mark are similar to those in Graph A, but results after the 30 minute mark are more apparent in Graph C. Similar to the group above, this graph shows how both oral ondansetron groups (with or without inhaled IPA) continue to have significant reductions in their nausea scores between 30 and 60 minutes, while the effects of using IPA inhalation alone leveled off after 30 minutes. This could be attributed to the 30-minute onset of action for oral ondansetron. However, despite the significant nausea score reduction after 30 minutes for participants receiving ondansetron, those receiving ondansetron alone still never reach the same total nausea score reduction as those receiving IPA.

The takeaway: it appears IPA inhalation alone or in combination with oral ondansetron was more effective than oral ondansetron alone at all measurement points. Additionally, IPA inhalation seemed to produce earlier benefits and “boost” the total effectiveness of oral ondansetron.

Mean nausea VAS scores from study administration until ED disposition, for patients with ED disposition less than 240 minutes. From April MD, et al.

Music

The American Music Therapy Association defines music therapy as: “The clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program.” Another term sometimes used in the literature is “music medicine,” which involves prerecorded music administered by medical or healthcare staff and preselected by study investigators, who may or may not have any formal training in music therapy. Based on the evidence, both approaches appear to be effective in certain situations.

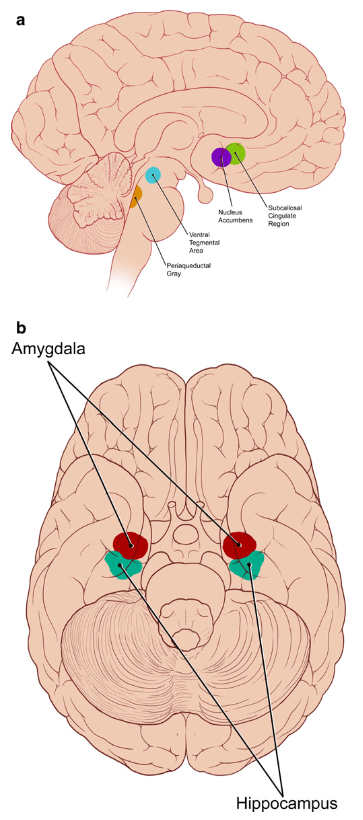

It appears that music is effective for pain, anxiety, and depression because it impacts areas of the brain that are rich in receptors for endogenous opioids and dopamine. Music’s effects on pain are demonstrated by a study that took place in a burn unit.³ Patients chose from 10 pieces of recorded non-lyrical instrumental music that they listened to for 30 minutes before and after their dressing changes; the study found that patient-selected music plus standard treatment reduced pain during the dressing changes. This study also found that while the overall frequency of analgesic use was not reduced, the type of analgesics used changed – there was a significant decrease in use of opioids, but an increase in use of non-opioids (e.g. acetaminophen, NSAIDs), which the authors attribute to lower levels of pain perception.

Illustration of the areas of the brain affected by music, and implicated in the pathophysiology of pain, anxiety, and/or depression. From Archie P, Bruera E, Cohen L.

In many situations, it is preferred for patients to listen to music via headphones – in the study just mentioned, headphones were used specifically to help block out the sounds of the burn unit. However, headphones are contraindicated in situations where the patient needs to hear the comments or directions of the medical team, because wearing headphones may make it difficult for the patient to hear these directions, which can increase the patient’s anxiety and in turn increase their perceived pain.

Aromatherapy and Music: Viable Adjunctive Therapies

As can be seen here, there are studies that seem to support the effectiveness of aromatherapy and music for certain symptoms in hospice and palliative care, although overall, a greater number and rigor of studies are needed. These therapies generally seem to be most effective as add-on measures to more traditional and/or medication therapies and are worth considering in a variety of patient situations.

Written by: Joelle Potts, PharmD, BCGP

References:

1. Grief CJ, Grossman D, Rootenberg M, Mah L. Attitudes of terminally ill older adults toward complementary and alternative medicine therapies. J Palliat Care. 2013 Winter; 29(4): 205-9. [Abstract]

2. April MD, et al. Aromatherapy versus oral ondansetron for antiemetic therapy among adult emergency department patients: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2018 Aug; 72(2): 184-93. Epub 2018 Feb 17.

3. Rohilla L, Agnihotri M, Trehan SK, Sharma RK, Ghai S. Effect of music therapy on pain perception, anxiety, and opioid use during dressing change among patients with burns in India: a quasi-experimental, cross-over pilot study. Ostomy Wound Management, 64(10), October 2018. 40-46. Available at: https://www.o-wm.com/article/effect-music-therapy-pain-perception-anxiety-and-opioid-use-during-dressing-change-among [last accessed 7/9/2020]

Additional References:

4. Deng G, Cassileth BR. Complementary therapies in pain management. Chapter in: Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine; 5th Edition, 2015. Editors: Cherny NI, Fallon MT, Kaasa S, Portenoy RK, Currow DC; Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom. 628-31.Grief CJ, Grossman D, Rootenberg M, Mah L. Attitudes of terminally ill older adults toward complementary and alternative medicine therapies. J Palliat Care. 2013 Winter; 29(4): 205-9. [Abstract]

5. Alliance of International Aromatherapists (AIA) website: www.alliance-aromatherapists.org [last accessed 7/31/2020]

6. National Association for Holistic Aromatherapy (NAHA) website: naha.org [last accessed 7/31/2020]

7. Ondansetron. Lexicomp (Lexi-Drugs) online. Wolters Kluwer, copyright UpToDate, Inc.; last updated 7/23/2020. [last accessed 7/31/2020]

8. American Music Therapy Association website: www.musictherapy.org [last accessed 6/27/2020]

9. Archie P, Bruera E, Cohen L. Music-based interventions in palliative care: a review of quantitative studies and neurobiological literature. Support Care Cancer. 2013; 21: 2609-24.

10. Bradt J, Dileo C, Magill L, Teague A. Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016, Issue 8. Art. No.: CD006911.