Opioids and Pain Management: Allergies, Conversions, Dysphagia, Oh My!

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

Pain is one of the most common symptoms we encounter as hospice clinicians, but it is also the most difficult to treat, particularly with opioid allergies, complex opioid conversions, and declining ability to swallow.

Opioid Allergies

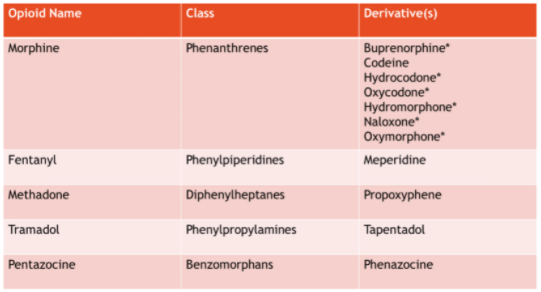

There are three different allergy subtypes, ranging from common adverse effects to true allergies, which are rare occurrences. Adverse effects are the most common and are defined as predictable effects based on the medication’s mechanism of action (e.g. nausea/vomiting, constipation, or drowsiness). Pseudo-allergies are unpredictable hypersensitivity reactions that occur after the first dose of an opioid and can range from itching to hives. True allergies are immune-mediated hypersensitivity reactions that occur after prior exposure or repeat dosing. Examples of severe true allergic reactions include: angioedema (swelling of the face, lips, and tongue), maculopapular rash, hypotension, and shock. Be sure to document the reaction type whenever possible for a complete allergy record and to ensure the safety of your patients upon switching to another opioid. There are five different chemical classes of opioids, and each class has a distinct chemical structure (Table 1). What this means is that even with a true allergy to one class of opioids, there should still be several options in another class to treat the patient’s pain.

Table 1 depicts the parent opioid in each class with its derivatives. If a patient has an allergic reaction to the parent drug, it’s likely that they may have that exact same reaction to a derivative.

*Decreased cross-tolerability within class

Conversions

It’s important to keep in mind that there isn’t a set formula for opioid conversions that works every time. Each calculation should be based on the individual patient, the amount of medications they are taking, pertinent history, and their goals for pain management. Consider following the steps below for a straightforward opioid conversion:

Step One: Convert all daily opioid usage from scheduled and PRN orders over to Oral Morphine Equivalents (OME).

Step Two: Use your hospice’s approved opioid conversion chart to convert between opioids.

(Example: Morphine to Hydromorphone; Tramadol to Oxycodone IR).

Please note that conversion to Fentanyl patches or Methadone requires use of medication-specific conversion charts.

Step Three: Reduce the final number by 25-33% to account for incomplete cross-tolerance.

Step Four: Double check your calculations, and when in doubt, call your friendly PHC pharmacist for help. Depending on the patient’s pain level and available dosage forms, you may round up or down.

Dysphagia

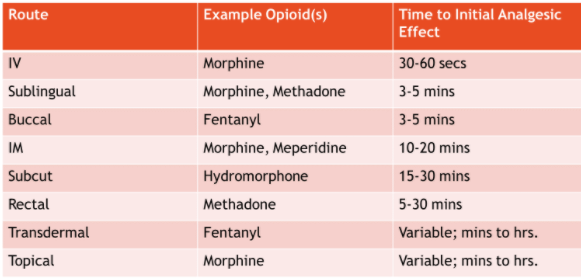

As patients approach end-of-life, up to 70% of patients require a non-oral route (NPO) for opioid administration. The non-oral routes that have the most supporting data are intravenous, subcutaneous, transdermal patches, and the enteral route. Routes with mixed supporting data are sublingual, buccal, rectal, and topical administration. Sublingual and rectal routes are used frequently in our patient population for convenience; however, absorption can be highly variable, depending on the medication used. The routes with the least supporting data are intramuscular injections, intravaginal, and intranasal.

Table 2 lists the various non-oral routes of administration, with examples of opioids that can be given via the route and the onset of action.

Pain management is complicated for our hospice and palliative care patients. As hospice clinicians, it’s imperative to ensure we anticipate a patient’s pain, double check conversion calculations, understand the nuances of opioid allergies, and pick the proper route of administration for maximum efficacy. This is truly the recipe for success, comfortable patients, and happy caregivers.

Written by: Meri Madison, Pharm.D.

References:

- Fudin J. Opioid Allergy, Pseudo-allergy, or Adverse Effect? US Pharm. 2018;3. Available Online from : https://www.pharmacytimes.com/contributor/jeffrey-fudin/2018/03/opioid-allergy-pseudo-allergy-or-adverse-effect.

- Fudin J. Chemical Classes of Opioids. Pain Dr. http://paindr.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Opioid-Structural-Classes-Figure_-updated-2018-02.pdf. Updated February 8, 2018.

- Gagnon B, Almahrezi A, Schreier G. Methadone in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain Res Manag. 2003;8:149-154.

- Manfredi PL, Houde RW. Prescribing methadone, a unique analgesic. J Support Oncol. 2003 Sep-Oct;1(3):216-20.

- Morley JS, Bridson J, Nash TP, et al. Low-dose methadone has an analgesic effect in neuropathic pain: a double-blind randomized controlled crossover trial. Palliat Med. 2003;17:576-587.

- Mercadante S, Casuccio A, Fulfaro F, Groff L, Boffi R, Villari P, Gebbia V, Ripamonti C. Switching from morphine to methadone to improve analgesia and tolerability in cancer patients: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2001 Jun 1;19(11):2898-904.

- Kestenbaum MG. et al. Alternative Routes to Oral Opioid Administration in Palliative Care: A Review and Clinical Summary. Pain Medicine 2014; 15: 1129–1153.

- Narang N and Sharma AJ. Sublingual mucosa as a route for systemic drug delivery. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2011. 3(Supply2); 15-22.

- Chang A et al. Transmucosal Immediate-Release Fentanyl for Breakthrough Cancer Pain: Opportunities and Challenges for Use in Palliative Care, Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy, 2015. 29:3, 247-260.

- Latuga NM et al. (2018) A Cost and Quality Analysis of Utilizing a Rectal Catheter for Medication Administration in End-of-Life Symptom Management, Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy, 32:2-3, 63-70.