Psychiatric Medication-Related Issues in Hospice

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

Medications used to treat psychiatric conditions and symptoms are commonly used in the hospice setting. It has been reported that antipsychotics are in the top 20 most frequently prescribed pharmacological class of medications in hospice patients. Adverse effects of these medications can easily be overlooked but can have significant effects on the patient. This article will examine adverse events associated with common psychiatric medications, including serotonin syndrome, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, extrapyramidal symptoms, and tardive dyskinesia.

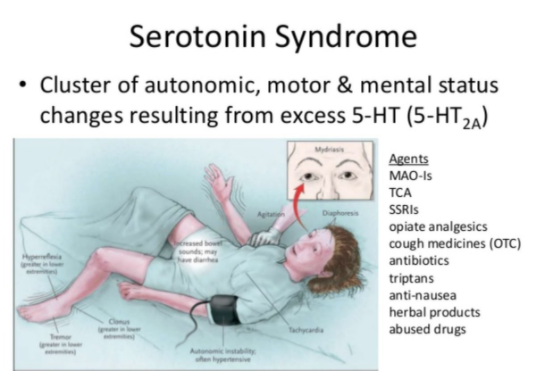

Serotonin Syndrome

With a substantial increase in antidepressant use in the United States over the last two decades, serotonin syndrome (SS) has become an increasingly common and significant clinical concern. Serotonin syndrome can be described as a progression of serotonergic toxicity based on increasing concentration levels of serotonin affecting the central and peripheral nervous systems. The classic presentation of SS is the triad of autonomic dysfunction, neuromuscular excitation, and altered mental status. Symptoms can range from tremor, twitching, and diaphoresis in mild serotonin toxicity, to severe myoclonus, seizures and multi-organ failure in severe toxicity.

Serotonin Syndrome. Retrieved from https://www.mycpdzw.org/common-emergencies-detail/50.

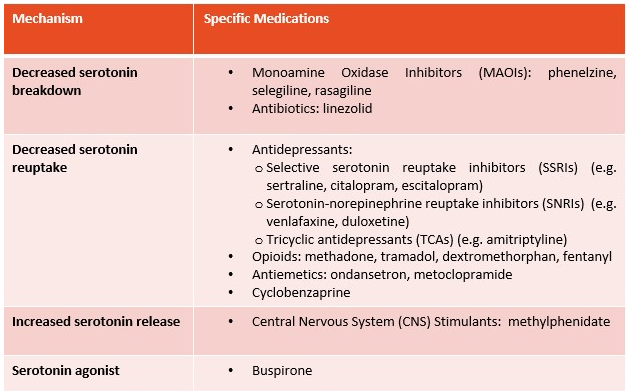

Medications most commonly associated with SS are classified according to mechanism in the following table.

The two mainstays of serotonin syndrome management are to discontinue the serotonergic agent and to give supportive care. Symptomatic treatment with a benzodiazepine, such as lorazepam or diazepam, is often used to treat agitation and clonus. Serotonin antagonists have had some success in case reports. Cyproheptadine and chlorpromazine have been used, but require further investigation beyond individual case reports to determine their effectiveness and reliability in treating serotonin syndrome.

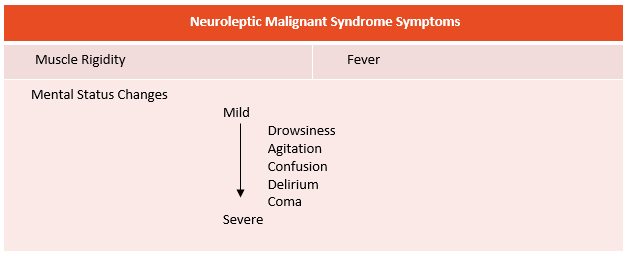

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a life-threatening idiosyncratic reaction to any medication that blocks dopamine, most commonly the antipsychotic drugs, but it can also happen with the rapid withdrawal of dopaminergic medications. The clinical course typically begins with muscle rigidity, also referred to as “lead-pipe” rigidity, followed by a fever within several hours of onset and mental status changes that can range from mild drowsiness, agitation, or confusion, to severe delirium or coma. See the following table of NMS symptoms.

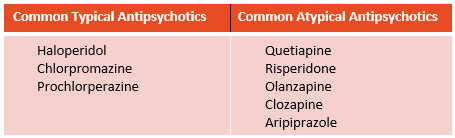

The primary trigger of NMS is dopamine receptor blockade and the standard causative agent is an antipsychotic. Potent typical antipsychotics such as haloperidol or chlorpromazine have been most frequently associated with NMS and thought to have the greatest risk (see table at bottom for typical and atypical antipsychotics). Although atypical antipsychotics appear to have a reduced risk of developing NMS compared to typical antipsychotics, a significant number of cases have been reported with some atypical antipsychotics including risperidone and olanzapine. NMS has also been associated with non-neuroleptic agents that have antidopaminergic activity such as metoclopramide. Another cause of NMS is the abrupt cessation or reduction in dose of dopaminergic medications such as levodopa in Parkinson’s disease.

When treating NMS, typically the first step in essentially all cases is discontinuing the causative neuroleptic medication (however, if the syndrome has occurred in the setting of an abrupt withdrawal of a dopaminergic medication, then this medication is reinstituted as quickly as possible). The next step is to give supportive therapy. The two most frequently used medications are bromocriptine mesylate, a dopamine agonist, and dantrolene sodium, a muscle relaxant. Anecdotal reports have shown these agents may shorten the course of the syndrome and possibly reduce mortality when used alone or in combination. Additional pharmacologic agents that may have some utility in treating NMS include benzodiazepines, which can be helpful in controlling anxiety and agitation.

Extrapyramidal Symptoms

A variety of movement disorders have been described along the spectrum of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), including dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonism. These symptoms are very debilitating for the patient, interfering with social functioning and communication, motor tasks, and activities of daily living. Dystonia most often occurs within 2-5 days of drug exposure and manifests with involuntary muscle contractions resulting in abnormal posturing or repetitive movements. Akathisia is characterized by a subjective feeling of internal restlessness and a compelling urge to move, leading to repetitive movements comprising leg crossing, swinging, or shifting from one foot to another. Drug-induced parkinsonism presents as tremor, rigidity, and slowing of motor function, or bradykinesia.

The medications most commonly associated with EPS are the centrally-acting, dopamine-receptor blocking agents, namely the first-generation (typical) antipsychotics, such as haloperidol. While EPS occurs less frequently with atypical antipsychotics, the risk increases with dose escalation. Other agents that block central dopaminergic receptors have also been identified as causative of EPS, including metoclopramide and prochlorperazine.

Managing EPS typically involves discontinuing the offending medication, or even switching to an atypical antipsychotic. Antimuscarinic medications, such as diphenhydramine, benztropine, or trihexyphenidyl, are also used to treat these symptoms. Akathisia can also be managed by use of the beta-blocker, propranolol, and parkinsonism symptoms can be treated with use of anti-Parkinson agents, such as levodopa or amantadine.

Tardive Dyskinesia

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a movement disorder that causes involuntary, repetitive body movements of the face, lips, tongue, trunk and extremities. It is most commonly seen in patients who are on long-term treatment with antipsychotic medications. The most common symptoms are orofacial dyskinesia and dyskinesia of the limbs. In many patients, TD is irreversible and can persist long after the causative medications are stopped.

Typical antipsychotics are the most likely to cause TD, while atypical antipsychotics seem to be associated with a decreased prevalence. Antidepressants, such as SSRIs and MAOIs are also associated with TD, but appear to have less risk than antipsychotics. Other medications that block dopamine, including metoclopramide and prochlorperazine, can also cause TD.

Management of TD involves discontinuing the offending agent. The FDA has approved a new class of medications called the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors, which are indicated for the treatment of TD in adults.

Examples of Typical and Atypical Antipsychotics

Among our hospice patients, use of these medications to treat various conditions at end-of-life is very prevalent. Symptoms of these adverse events can easily be overlooked or misattributed to be ‘part of the dying process’. Thus, knowledge of these adverse events is critical when evaluating patient symptoms while taking these medications, to prevent further morbidity. When in doubt, a ProCare clinical pharmacist, available 24/7/365, can help assess the possibility of an adverse event from a psychiatric medication, and can assist in its management.

Written by: Kiran Hamid, R.Ph.

References

- Wang, R. et al. (2016, November). Serotonin syndrome: Preventing, recognizing, and treating it. Retrieved from https://www.mdedge.com/ccjm/article/120386/neurology/serotonin-syndrome-preventing-recognizing-and-treating-it/page/0/1

- Boyer, E. (2018, March 12). Serotonin syndrome (serotonin toxicity). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/serotonin-syndrome-serotonin-toxicity

- Berman, B. (2011, January). Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome: A Review for Neurohospitalists. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3726098/

- Wijdicks, E. (2019, May 31). Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/neuroleptic-malignant-syndrome

- D’Souza, R. Hooten, W. M. (2019, January 9). Extrapyramidal Symptoms (EPS). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534115/.

- Jackson, N. et al. (2008, March) Neuropsychiatric complications of commonly used palliative care drugs. Retrieved from https://pmj.bmj.com/content/84/989/121.full

- Cornett, E. et al. (2017, July). Medication-Induced Tardive Dyskinesia: A Review and Update. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5472076/

- Muench, J. Hamer, A. (2010, March 1). Adverse Effects of Antipsychotic Medications. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/afp/2010/0301/p617.html.

- Ferguson, J. (2001, February). SSRI Antidepressant Medications: Adverse Effects and Tolerability. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC181155/

- Serotonin Syndrome. Accessed 9/25/19. Retrieved from https://www.mycpdzw.org/common-emergencies-detail/50.

- Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome. Accessed 9/25/19. Retrieved from http://klossandbruce.com/video-flashcard-neuroleptic-malignant-syndrome