Constipation: When Your Patient Can’t “Enjoy the Go”

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

Overview

Constipation is a common gastrointestinal complaint. It consists of less than three bowel movements per week, and stools that may be hard, dry, lumpy, and difficult or painful to pass. Some patients may feel that not all of the stool has passed after having a bowel movement.¹ Dehydration, bowel motility, and lubrication can also affect bowel movements.⁴

Non-Pharmacological Treatments

Diet and lifestyle changes like increasing fiber, fluids, and activity are not appropriate for many hospice patients. If a patient is on opioids, has minimal fluid intake or poor gut motility, fiber can actually worsen the situation, or even cause an obstruction.⁴

If possible, educate patients to go to the bathroom as soon as they feel the need to defecate. Optimal times are after waking and after meals. The patient’s perception may also need to be altered. As they decline, it may no longer be realistic or appropriate to have bowel movements with the same regularity that they had before.³

Pharmacological Treatments

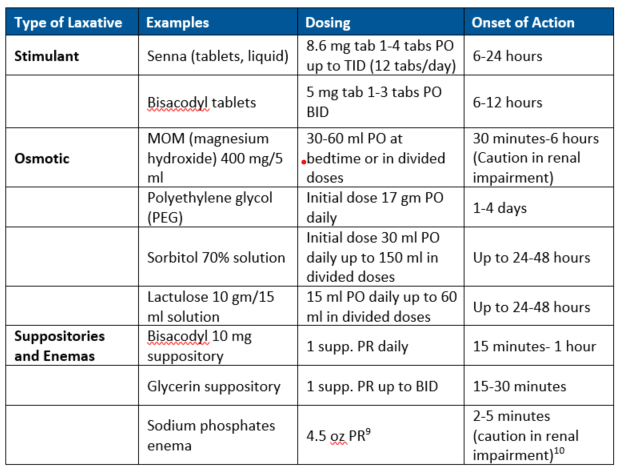

For patient with hard stools, utilize osmotic agents which include magnesium salts, polyethylene glycol (PEG), sorbitol, and lactulose (reserve for patients with hyperammonemia, sorbitol is better tolerated and more cost effective than lactulose).

The stool softener docusate sodium (Colace®) is not included in the list above. There is no evidence that docusate sodium is effective for constipation. Multiple randomized controlled trials have failed to show any significant efficacy of docusate sodium over placebo. These trials have included hospital, nursing home, hospice, and ambulatory patients.⁵ Continuing docusate sodium, even though the drug itself doesn’t work, has many negative downstream effects, including, but not limited to, creating extra work for the nurse, caregiver, families and patients. Along with increased pill burden and a delay in obtaining effective treatment of constipation, if a patient is having difficulty swallowing medications, they may take docusate sodium over an important comfort medication.⁶ Note, docusate liquid has been known to taste terrible.⁷ If a patient is on the combination product senna/docusate sodium 8.6-100 mg tablet, this can be replaced with plain senna 8.6 mg tablet.⁶ Let’s stop flushing good money down the toilet with habitual use of a laxative (docusate sodium) that doesn’t work.⁷

Stimulant laxatives are used when patients are having motility issues. Oral senna is preferred and the tablets can be crushed. It is also available in liquid and tea form. Bisacodyl is another stimulant laxative available in tablets and suppositories. The suppositories can be used daily or as needed (prn) for constipation.⁴

Lubricant laxatives can be used in patients having painful bowel movements. Mineral oil is a lubricant and available as an enema. It is not recommended to be given orally as pneumonitis can result if it is aspirated. Glycerin suppositories are another lubricant laxative with the added benefit of drawing water into the rectum.⁴

Opioid Induced Constipation (OIC)

Opioid induced constipation (OIC) affects 45-90% of patients on opioids. Patients do not develop tolerance to OIC like most other side effects. Also, there is no evidence that physical activity, scheduled toileting, fiber, or adequate fluid intake are effective. Opioids cause constipation using multiple mechanisms. They affect GI motility, inhibit mucosal transport of electrolytes and fluids, and interfere with the defecation reflex.⁸

Stimulant and osmotic laxatives are effective for opioid-induced constipation (OIC). The preferred oral stimulant is senna. Bisacodyl is also available orally.⁹ Rectal-based laxatives are often used when oral options fail. Warm tap water and milk of molasses enemas can also be used, and can be dosed more frequently (up to every 2 hours).⁸

Refractory Constipation

For refractory constipation, suppositories and enemas can be used. As a last resort, manual evacuation can be done.⁸

If there is a high impaction that has failed to be relieved with other treatments, Vaseline balls can be used. Freeze a dollop of Vaseline, roll/squeeze into pea-sized balls, roll in confectioners’ sugar or cocoa powder for taste. Have the patient swallow 1-2 balls q3-4 hours until BM, may increase if no BM in 12 hours.⁹

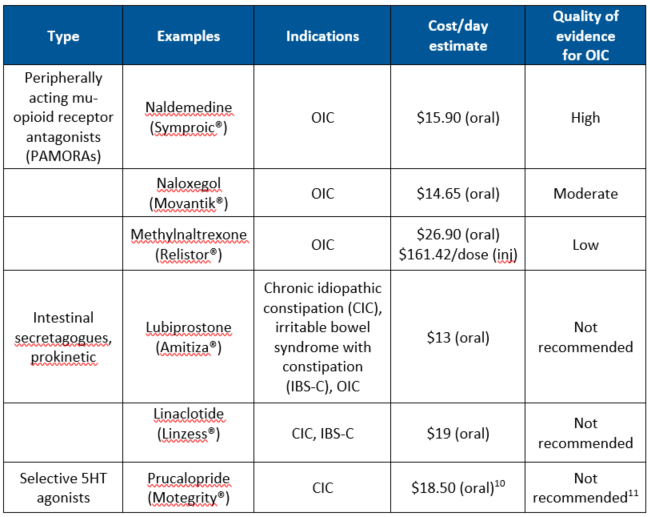

Newer Agents for Constipation

There are some newer agents for OIC as well as other types of constipation. However, the first-line agents for constipation are the traditional laxatives. This includes OIC. The traditional laxatives are proven safe and effective, and are also extremely cost effective when compared to the newer agents.

In summary, identify patients who are at risk for constipation and initiate a bowel regimen. All patients on opioids are at risk. Target the cause, when possible. Most elderly patients have complex constipation and OIC has multiple causes, so multiple agents may be needed. Stimulants and osmotics are usually the best options. When needed, utilize suppositories and enemas. Make sure to titrate to maximum doses (senna 8.6 mg tab up to 12 tabs/day, 4 tabs po tid), and if needed, add on other routine (sorbitol) or prn laxatives (mom, suppositories etc.). Newer agents should only be tried after an adequate trial (titrated to maximum doses) of the appropriate traditional laxatives.

Written by Karen Bruestle-Wallace, PharmD, BCGP, RPh

References

- Lacy, B. E. (Ed.). (2018, May). Constipation. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/constipation.

- 3 in PowerPoint. Sonnenberg, A., & Koch, T. R. (1989, January). Epidemiology of constipation in the United States. Diseases of the colon and rectum. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2910654/.

- 4 in PowerPoint De Giorgio, R., Ruggeri, E., Stanghellini, V., Eusebi, L. H., Bazzoli, F., & Chiarioni, G. (2015). Chronic constipation in the elderly: A Primer for the Gastroenterologist. BMC Gastroenterology, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-015-0366-3

- 5 in PowerPoint Hallenbeck, J. (2015, May). Fast facts and concepts #15 constipation James Hallenbeck ... FAST FACTS AND CONCEPTS #15 CONSTIPATION. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://www.mypcnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/FF-15-Constipation.-3rd-ed.pdf.

- 6 in PowerPoint Fakheri, R. J., & Volpicelli, F. M. (2019). Things we do for no reason: Prescribing docusate for constipation in hospitalized adults. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 14(2), 110–113. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3124

- 7 in PowerPoint Lee, T. C., McDonald, E. G., Bonnici, A., & Tamblyn, R. (2016). Pattern of inpatient laxative use. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(8), 1216. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2775

- McKee, K. Y., & Widera, E. (2016). Habitual prescribing of laxatives—it’s time to flush outdated protocols down the drain. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(8), 1217. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2780

- Badke, A., & Rosielle, D. A. (2015, April). FF and Concepts #294 Opioid Induced Constipation Part 1: Established Management Strategies. FF-294 Opioid Constipation. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://www.mypcnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/FF-294-opioid-constipation-.pdf.

- Shah, S.; Madison, M.; Speer, K. ProCare HospiceCare, Hospice Medication Utilization Guidelines (HUGS). Gainesville, GA

- Lexicomp Online, Lexi-Drugs, Waltham, MA: UpToDate, Inc.; Oct. 18, 2021. https://online.lexi.com. Accessed Oct 20, 2021.

- Crockett, S. D., Greer, K. B., Heidelbaugh, J. J., Falck-Ytter, Y., Hanson, B. J., & Sultan, S. (2019). American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the Medical Management of opioid-induced constipation. Gastroenterology, 156(1), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.016