The Use of Medical Marijuana in Hospice and Palliative Care

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

Cannabis (marijuana) has recently garnered significant national attention as more states vote to legalize both medicinal and recreational forms of the substance. Cannabis use in end-of-life care is increasingly being sought by patients, and organizations are caught between strict federal regulations and waning state laws. Many states have legalized marijuana’s medical use and some have recognized its recreational use as well. However, federally, it is still a Schedule I substance.

Cannabinoids and the Endocannabinoid System

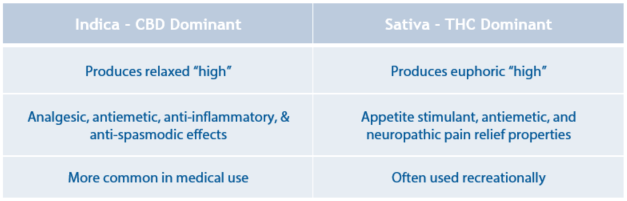

Cannabis exerts its effects on the body by interacting with the endocannabinoid system, which consists of cannabinoid (CB) receptors. There are two main CB receptors in the body, the CB1 and the CB2. CB1 receptors can mainly be found in the brain and spinal cord, whereas the CB2 receptors are mostly located in the periphery. More than a hundred cannabinoids have been identified in the marijuana plant. Of these, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) have been studied most extensively. THC is thought to interact mostly with the CB1 receptor, whereas CBD seems to have an effect on both the CB1 and CB2 receptors. Furthermore, cannabis can be divided into two primary species: indica and sativa. Indica strains are more CBD dominant, so it binds to CB1 and CB2 receptors, causing increased mental and muscle relaxation. The sativa strain is more THC dominant and is more commonly used for recreational purposes.

Medical Uses of Cannabis

When a state approves the use of cannabis for medicinal purposes, the patient must meet certain criteria in order to be able to use medical marijuana. One of these criteria is a qualifying condition. There are many qualifying conditions for which several states have approved the use of medical marijuana, but evidence that marijuana is actually effective for these conditions is limited. It’s thought that cannabis may play a role in symptom management in neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease. Studies have found that cannabis helps improve patient-reported symptoms of spasticity and pain associated with multiple sclerosis.

Additionally, cannabis appears to have a role in treating chemotherapy-induced nausea/ vomiting. Marinol® (dronabinol) is a synthetic THC derivative that is FDA approved for the treatment of chemotherapy–induced nausea/vomiting. It also has indications to treat anorexia in AIDS patients. However, since it is a THC derivative, its most frequently reported adverse effect is euphoria.

It is also thought that cannabis may be effective for pain management. Interestingly, there is some evidence that shows cannabis may be effective for refractory neuropathic pain in cancer and in patients with multiple sclerosis. However, some recent studies have shown that the use of cannabis for cancer pain was no better than placebo, and not effective for this type of pain.

Cannabis also appears to have a role in seizure management. In 2018, Epidiolex®, the first US-approved drug made solely from plant-grown cannabis, was approved for specific, rare types of epilepsy.

Routes of Administration

Laws and Regulations Concerning Cannabis Use

Although many states have started to legalize marijuana for medical use, it is still classified as a Schedule I substance at the federal level. As a hospice organization, it is illegal to furnish patients with cannabis. If your patient is taking marijuana for medical purposes, it should be documented and the patient should be offered evidence-based information regarding medical marijuana, but it cannot be provided by the hospice. In those states where medical marijuana is legal, only physicians that are specially certified by the state are able to recommend this substance for their patients who meet certain criteria. Also, marijuana is a cash-only market, which makes payment difficult, and government reimbursement should not be used to reimburse the patient or family.

Within facilities, laws regarding medical marijuana use, storage and administration can depend on state laws and also individual facility policies – it may even depend on what type of facility it is. Many nursing homes, for example, are regulated and funded by the federal government, and are concerned that non-compliance with federal law by allowing cannabis, may result in loss of funding. The past several decades have shown an increase in the use of medical marijuana. As a growing number of states vote to legalize its medicinal use, there is hope that there will be more research done to show its evidence based use and to further define its role in hospice and palliative care.

Written by Kiran Hamid, RPh

References:

Aggarwal SK, “Use of cannabinoids in cancer care: palliative care”, Curr Oncol. 2016 Mar; 23(Suppl 2): S33–S36.

Bereseford L, “How should Hospices Handle Legalized Marijuana” The Lancet, 19 Oct 2016

Häuser W, Fitzcharles M, Radbruch L, Petzke F, “Cannabinoids in Pain Management and Palliative Medicine: An Overview of Systematic Reviews and Prospective Observational Studies, Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017 Sep; 114(38): 627–634.

https://inhalemd.com/blog/medical-marijuana-allowed-nursing-homes-assisted-living-communities/

Cannabinoids No Help for Cancer Pain, Concludes Meta-Analysis - Medscape - Jan 29, 2020.