Deprescribing and Optimizing Medication Use

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

The Lown Institute has identified medication overload, or polypharmacy, as a threat to the future of our healthcare system. Researchers found that almost 20% of older adults take 10 or more medications per day. The more medications a patient takes, the greater the risk of complications. The US is on track to spend $62 billion on hospitalizations due to adverse drug events over the next 10 years. The good news is that hospice and palliative care clinicians are uniquely positioned to be part of the solution. Nurses and physicians can emphasize the importance of medication reviews and deprescribing to patients and families to stop these projections from becoming statistics.

Deprescribing

Deprescribing is the systematic process of identifying and discontinuing medications based on the patient’s prognosis and specific goals of care. This practice is most helpful with a life expectancy of a year or less, or when an adverse medication effect is suspected. For best results, it is recommended to take a step-wise approach to deprescribing:

- Start with a comprehensive list of medications; ideally upon admission

- Identify potential medications to be tapered off and/or discontinued

- Develop a plan for tapering and/or discontinuation of targeted medications

- Monitor closely for withdrawal symptoms

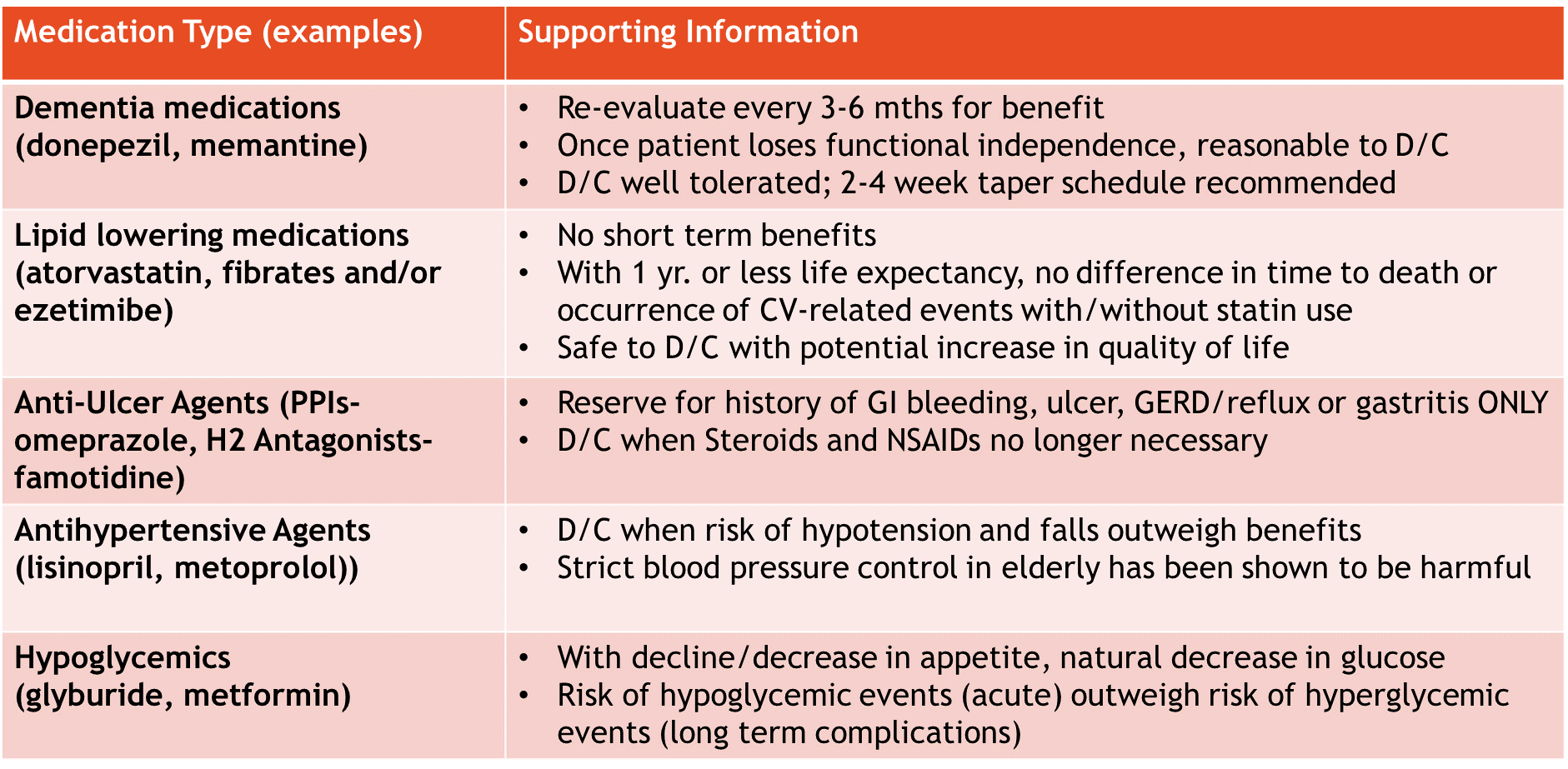

When a patient’s Palliative Performance Score (PPS) drops below 40%, it is reasonable to begin discontinuing unnecessary medications. The most commonly discontinued medication classes include, but are not limited to statins, multivitamins/supplements, proton pump inhibitors, thyroid medications, respiratory inhalers, anti-hypertensives, anticoagulants, anti-depressants, and dementia medications. With chronic medication use, patients become physically and emotionally attached. It is helpful to have supporting information when discussing deprescribing plans with patients/families. Below are a few medication types and supporting information for discontinuation:

Medication Optimization

In hospice and palliative care, the goals of care shift from curative to comfort through symptom control.

Below are several strategies to aid in optimizing a patient’s medication regimen at end-of-life:

- Review medication list and determine what is reasonable and necessary to continue for symptom management related to the terminal illness and related conditions, per CMS §418.200 Conditions of Participation⁵

- Is atorvastatin for cholesterol reasonable and necessary for symptoms in lung cancer?

- Individual patient assessment

- Examine your patient’s Palliative Performance Score, swallowing ability, appetite, etc.

- Plan ahead and use anticipatory prescribing

- Utilize standing orders and comfort care kits

- Use routine and PRN orders to control symptoms more effectively

- Ex: Morphine ER for long-acting pain relief and Morphine IR for breakthrough pain

- Minimize pill burden through use of medications that treat multiple systems

- Ex: Prednisone for pain, inflammation, appetite, and energy

- Continually review and monitor symptom medications for effectiveness

- Ask the following: Is this still the right medication? The right dose? Is the indication still appropriate?

The overall goal of medication review is to ensure the patient has the best quality of life possible in their remaining days. At the end of the day, our patients are more than just a medication list; they each have unique and important goals of care. Hospice clinicians are well-positioned to advocate for their patients’ best interests and cater to those goals to create a lasting impact when it counts the most.

For more information, check out these tools/criteria for medication review:

Deprescribing: www.deprescribing.org

Beers Criteria: https://bit.ly/2GQhM2Y

Medication Appropriateness Index: https://41e5fc1d-e404-4830-8c07-64690e79acce.filesusr.com/ugd/2a1cfa_92f7abde530844aaa6bd44ac57a413b3.pdf

Good Palliative Geriatric Practice Algorithm: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-Good-Palliative-Geriatric-Practice-GPGP-algorithm-D-Garfinkel-S-Zur-Gil-J_fig3_304143731

Written by: Meri Madison, PharmD, RPh

References

1. Lown Institute. Medication overload and older Americans. Available from: https://lowninstitute.org/projects/medication-overload-how-the-drive-to-prescribe-is-harming-older-americans/.

2. Endsley, S. Deprescribing Unnecessary Medications: A Four-Part Process. Fam Pract Manag. 2018;25 (3):28-32.

3. Thompson J. Deprescribing in palliative care. Clinical Medicine 2019 Vol 19. No 4: 311-14.

4. Kim LD, Factora RM. Alzheimer’s dementia: Starting, stopping drug therapy. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine March 2018, 85 (3) 209-214; Available from: https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.85a.16080.

5. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. Part 418 Hospice Care. Available from: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=1e60a115cd2f086b2c32af0cce72353d&mc=true&node=pt42.3.418&rgn=div5#se42.3.418_154.

6. Van Den Noortgate, Nele J. et al. Prescription and Deprescription of Medication During the Last 48 Hours of Life: Multicenter Study in 23 Acute Geriatric Wards in Flanders, Belgium. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, Volume 51, Issue 6, 1020 – 1026.

7. Todd, Adam, and Holly M. Holmes. “Recommendations to Support Deprescribing Medications Late in Life.” International journal of clinical pharmacy 37.5 (2015): 678–681. PMC. Web. 2 Aug. 2018.

8. Pruskowski, J. Fast Facts and Concepts #321 Deprescribing. Available from: https://www.mypcnow.org/copy-of-fast-fact-320. Accessed 2 August 2018.