Managing Opioids for Pain and Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia in an Opioid Crisis Society

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

In the US, drug overdose is the leading cause of death for persons under age 50, and those between ages 18-25 are the most likely to use addictive drugs. Nine out of 10 people with substance problems started using by age 18. Those aged 18-25 years with substance use disorder (SUD) report getting 37.5% of their opioids from a friend or relative for free, and 19.9% report getting them from a friend or relative that they pay.

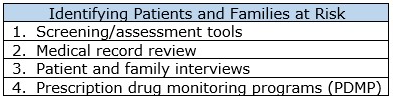

The previous statistics illustrate the importance of maintaining tight control on opioids in order to help fight the opioid crisis. It is important to identify patients and families at risk of opioid misuse or diversion (see Table 1). Additional steps can then be taken to ensure opioids are kept out of the wrong hands.

Screening and assessment tools are not specific to hospice patients. They can be used as they are, or as a resource for designing your own tools and questions. The Opioid Risk Tool(ORT) https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/OpioidRiskTool.pdf is designed to be used before starting long-term opioid therapy. Positive responses are weighted and added up to indicate the patient’s risk for opioid abuse. The Addiction Behaviors Checklist (ABC) is a tool that can be used for patients currently taking opioids https://www.nhms.org/sites/default/files/Pdfs/Addiction_Behaviors_Checklist-2.pdf. It examines addiction behaviors during each provider visit, and behaviors since the last visit. A score of 3 or greater indicates possible opioid misuse. Further evaluation, closer monitoring and increased accountability measures may be needed for patients scoring 3 or above.

Pain Management Agreements or Treatment Agreements are a good way to promote understanding regarding the patient's and hospice’s roles and responsibilities surrounding opioids and other controlled substances. They should facilitate communication and involve caregivers and family members if appropriate.

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH) is a complication of opioid use and abuse that is just starting to be recognized clinically. It is more common with high dose opioids, though it can occur even in patients who are opioid naïve. It can also occur in patients with a history of opioid abuse. OIH occurs in acute and chronic pain, and also in malignant and non-malignant conditions. Fentanyl and morphine are the opioids with greatest risk, but OIH is also reported with high dose oxycodone.

In order to diagnose OIH, confounding factors must be ruled out. These include tolerance, disease progression, withdrawal hyperalgesia, pain unresponsive to opioid therapy, and opioid-induced androgen deficiency. Signs of OIH include an increase in pain sensitivity, worsening pain with increased opioid dose, sensitivity to painful, as well as non-painful, stimuli, and diffuse pain.

There are different options to manage OIH. In rapid dose reduction, the opioid is decreased by 20-50% the first day, then 10-20% every day depending on patient response and goals of therapy. The dose can also be decreased by 40-50% and low dose (adjunct) methadone can be added if appropriate, as it is known to work differently from other opioids, and can reduce OIH. Opioid rotation is also an option. If the patient is on morphine or hydromorphone, they potentially could be rotated to methadone or fentanyl, if not contraindicated. Methadone may be appropriate and effective for some patients. The off-label use of low dose ketamine (a non-opioid medication) and a reduction in the opioid dose shows promise as another way to manage OIH. Both Methadone and Ketamine can be given by many different routes; the oral route is most convenient for hospice patients. Dosing and titration is complex and based on individual patient factors. Coordination with the patient’s medical provider is critical and a ProCare pharmacist can provide information to facilitate your decision about whether methadone and/or ketamine would be appropriate.

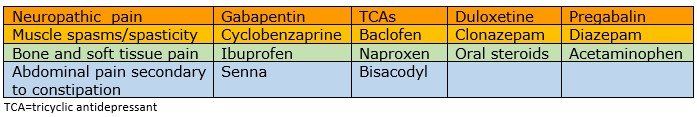

Other non-opioid analgesics or adjuvants should also be utilized for pain that is unresponsive to opioids (though methadone can be an exception, as this opioid is effective for neuropathic pain where other opioids are not). See Table 2.

In summary, procedures need to be in place to identify patients at risk for opioid misuse, patients who are misusing opioids, and environments at risk for drug diversion. Treatment agreements and appropriate controls need to be in place to help control the opioid crisis. And if a patient’s pain is not being managed well with opioids, clinicians needs to assess for possible OIH vs other challenges or confounders.

Please contact a ProCare Clinical Pharmacist, 24/7, for guidance on how to manage suspected or confirmed opioid abuse or symptoms of OIH.

Written by: Karen Bruestle-Wallace, Pharm D, BCGP

References:

- (DHHS/PHS), S. A. and M. H. S. A. (2012). Managing Chronic Pain in Adults with or in Recovery from Substance Use Disorders. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 54. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://doi.org/(SMA) 12-4671

- Carullo, V., Fitz-James, I., & Delphin, E. (2015). Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: A diagnostic dilemma. Journal of Pain and Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy, 29(4), 378–384. https://doi.org/10.3109/15360288.2015.1082006

- Cheattle, M. D. (2019). Risk Assessment: Safe Opioid Prescribing Tools. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from PPM Practical Pain Management website: https://www.practicalpainmanagement.com/resource-centers/opioid-prescribing-monitoring/risk-assessment-safe-opioid-prescribing-tools

- Kaplan, S. (2017). C.D.C. Reports a Record Jump in Drug Overdose Deaths Last Year - The New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2020, from The New York Times website: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/03/health/deaths-drug-overdose-cdc.html

- Key Ph.D., K. (2017). Drug Overdoses are Leading Cause of Death for those under 50 | Psychology Today. Retrieved February 23, 2020, from Psychology Today website: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/counseling-keys/201711/drug-overdoses-are-leading-cause-death-those-under-50

- Nathan, Y. (2019). Addiction Statistics - Facts on Drug and Alcohol Use - Addiction Center. Retrieved February 23, 2020, from https://www.addictioncenter.com/addiction/addiction-statistics/

- ProCare HospiceCare. (2016). Ketamine Use – Quick Guide. Gainesville, GA.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2016). Opioid Taper Decision Tool. 1–16. Retrieved from https://vaww.portal2.va.gov/sites/ad/SitePages/Home.aspx

- Wall, J., & Chauhan, A. (2018). A Case of Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia. Journal of Pain and Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy, 32(2–3), 158–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/15360288.2018.1546256

READY TO START A CONVERSATION?

Request a Live Demo and Find Out How Your Organization can be ‘Powered by ProCare Rx’

All Rights Reserved | Burgess Information Systems