Lung Cancer Symptom Management at the End of Life

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

Lung cancer is the second leading cause of all deaths in the United States. It is the second most common type of cancer, but the number one cause of cancer deaths. The primary risk factor, cigarette smoking, is estimated to attribute to 90% of lung cancer cases. This includes cases related to second-hand smoke.

Common symptoms in end-stage lung cancer include dyspnea, cough, and hemoptysis. Additional symptoms include, but are not limited to, wheezing, hoarseness, pain, weight loss, and weakness. We will discuss the more common symptoms and treatment strategies below:

Dyspnea

Dyspnea, also called labored or difficult breathing, is a common symptom in many lung cancer patients. Wheezing is often associated with difficulty breathing. Some potential causes of dyspnea include blocked airways, pleural effusion, and hypoxemia. It is helpful if the cause can be identified, then treatment that targets the cause can be selected.

COPD, asthma, and tumors can lead to blocked airways. Bronchodilators, anticholinergics, and steroids can be used to treat dyspnea associated with COPD, asthma, or tumors that block airways. COPD and asthma patients typically come to hospice on inhalers that may combine some or all of these drug classes. A recent study showed that 45% of COPD patients made at least one error when using their inhalers (Lindh, A. et. al., 2019). We would expect our hospice patients, who are usually weaker and may have multiple comorbidities, to make even more improper-use errors. These errors lead to decreased efficacy and a possible increase in side effects. Inhalers are also very costly. Because of these issues, nebulizers are preferred over inhalers for increased efficacy and a decrease in cost and potential side effects. Addition of oral steroids to the nebulized therapies can provide additional benefits.

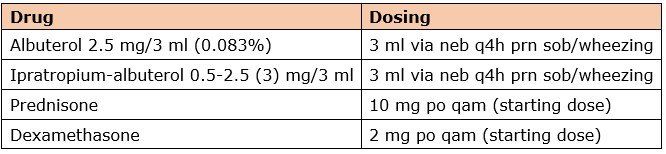

The preferred inhaled bronchodilator, anticholinergics, and oral steroids are listed here with usual doses:

Albuterol or ipratropium-albuterol via nebulizer should be scheduled three or four times daily to replace a routine inhaler regimen containing a bronchodilator. A scheduled nebulizer regimen is often preferred for patients experiencing severe dyspnea. Ipratropium can be administered alone for patients who cannot tolerate albuterol.

Mucus or phlegm can also block airways. Guaifenesin is a first-line agent used to thin the mucus so the patient can clear it more effectively. Guaifenesin is available in 600 and 1200 mg Extended Release (ER) tablets dosed every 12 hours. Immediate Release (IR) tablets come in 200 and 400 mg, and liquid is also available. IR formulations are dosed 200 to 400 mg orally every 4 hours as needed for chest congestion. Guaifenesin can also be scheduled if desired.

If pleural effusions are causing dyspnea, they should be drained where appropriate. If hypoxemia is causing dyspnea, supplemental oxygen should be utilized. There are some non-pharmacologic treatments that may also help dyspnea. They include cool air (using a fan, opening windows), relaxation exercises, and meditation.

When a patient experiences refractory dyspnea, opioids are the drugs of choice. Morphine is first-line if not contraindicated. The usual dose for morphine 20 mg/mL oral liquid is 5 mg orally or sublingually every 2 hours as needed for dyspnea. Alternatives include oxycodone IR and hydromorphone IR (tablets preferred; may be crushed). Dyspnea usually responds better with lower doses of opioid given more frequently. However, if a patient is taking many PRN opioid doses for shortness of breath each day, the addition of long-acting opioids may be considered. Long-acting opioids are often helpful if a patient is waking up at night with shortness of breath.

Anxiolytics are used to treat the anxiety that is related to dyspnea. They have no direct effect on dyspnea, so they should not be used alone for shortness of breath. A lorazepam 0.5 mg tab given orally every 4 hours as needed is preferred because it is a less risky alternative than other benzodiazepines due to lack of active metabolites and a shorter duration of action.

Cough

Cough can be a very troublesome symptom in lung cancer. If the underlying cause can be determined, treatment can be targeted to stop or control the cough. Some things that can cause cough are excess mucus, inflammatory secretions, blood in the airways, and tumor infiltration of the bronchus. Some patients will also have an idiopathic cough.

If excess mucus is causing a cough, we want to identify if the cough is productive or non-productive. If the cough is productive, our goal is to thin the mucus so the patient can clear it. Guaifenesin, an expectorant, is our first-line treatment. Dosing was discussed above. If guaifenesin is ineffective, normal saline via nebulizer can be tried to thin secretions. For best results, use normal saline nebulizers 30 minutes after a bronchodilator (albuterol) or anticholinergic (ipratropium) every 4 hours as needed, and it can be scheduled. It is also helpful if the patient is able to drink more fluids to combat excess mucus and to help thin it out.

If the cough is non-productive or the patient is too weak to cough up the excess sputum, anticholinergics like hyoscyamine 0.125 mg orally or sublingually every 4 hours as needed or ipratropium 0.02% via nebulizer every 4 hours as needed can be used.

If cough is suspected to be caused by tumor infiltration of the bronchus or is related to chronic bronchitis, oral steroids can be used. Prednisone or dexamethasone are preferred. Prednisone can sometimes worsen edema; if this occurs, dexamethasone is a better choice. Dexamethasone is also used if the patient has a brain tumor, as dexamethasone penetrates the blood-brain barrier and helps treat inflammation associated with the brain tumor. The starting dose for prednisone is typically 10 mg orally every morning, and for dexamethasone, it is 2 mg orally every morning.

Cough suppressants are used to control the severity of the cough. Guaifenesin-dextromethorphan 100-10 mg/5 mL can be given as 10 mL orally every 4 hours as needed for cough. If this is not effective, an opioid can be added. Guaifenesin-codeine 100-10 mg/5 mL can be given as 10 mL orally every 4 hours as needed, or hydrocodone-homatropine 5-1.5 mg/5 mL can be given as 5 mL orally every 4-6 hours as needed.

For patients having trouble sleeping because the cough is waking them up at night, longer-acting cough suppressants can be tried. A couple of common ones: benzonatate 100-200 mg orally three times daily as needed, or dextromethorphan 30 mg/5 mL ER liquid given as 10 mL orally every 12 hours as needed for cough.

For idiopathic refractory cough, gabapentin has been used successfully. Note that cough is an off-label use of gabapentin. The starting dose is 300 mg orally at bedtime. If this dose is not effective it may be increased in increments of 300 mg once or twice daily. If needed, further increases can be made gradually up to 900 mg twice daily, while closely evaluating effect and tolerability.

Hemoptysis

Hemoptysis, or blood in the bronchial secretions, occurs in about 20% of lung cancer patients. Pulmonary hemorrhage occurs in around 3% of patients and, unfortunately, often ends in death. Some possible causes of hemoptysis are anticoagulation therapy, pulmonary embolism, and bronchiectasis.

Treatment of hemoptysis includes cough suppressants (discussed above) and discontinuing anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents. Additional measures to minimize the impact of hemoptysis might include positioning the patient to prevent choking, utilizing dark colored bed linens, and the use of anxiolytics, such as lorazepam.

In conclusion, for patients with dyspnea and cough, identify the underlying cause if possible. This will guide better treatment selection. Steroids can be used to treat a variety of conditions when appropriate, thus minimizing pill burden. Nebulizers, with or without steroids, are preferred over inhalers in most hospice patients due to inadequate inhaler technique, inability to take a deep breath, and possible increase in side effects. Anxiolytics should not be used alone for dyspnea. They have no direct effect on dyspnea, but do help reduce the anxiety that can exacerbate dyspnea. Opioids may be used concurrently with other therapies to manage refractory dyspnea.

Consult your ProCare Clinical Pharmacist team any time, 24/7/365, to help manage lung cancer symptoms. We can identify alternative patient-specific therapies to help patients breathe easier while keeping your medication costs lower!

Written by: Karen Bruestle-Wallace, PharmD.

References

1. American Cancer Society (2018). Lung Cancer- Non-Small Cell: Statistics. Net. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/lung-cancer-non-small-cell/statistics

2. Siddiqui, F.; Siddiqui, H. (2020). Lung Cancer StatPearls. NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482357/

3. Lim, R. B. (2016). End-of-life care in patients with advanced lung cancer. Therapeutic Advances in Respiratory Disease,10(5), 455-467. doi:10.1177/1753465816660925

4. Farbicka, P., & Nowicki, A. (2013). Reviews Palliative care in patients with lung cancer. Współczesna Onkologia,3, 238-245. doi:10.5114/wo.2013.35033

5. Lexicomp Online, Lexi-Drugs Online, Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp, Inc.; October 20, 2020.

6. Lindh, A., Theander, K., Arne, M., Lisspers, K., Lundh, L., Sandelowsky, H., . . . Zakrisson, A. (2019). Errors in inhaler use related to devices and to inhalation technique among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary health care. Nursing Open,6(4), 1519-1527. doi:10.1002/nop2.357

7. Razzak, R., Waldfogel, J. M., Doberman, D. J., Feliciano, J. L., & Smith, T. J. (2017). Gabapentin for Cough in Cancer. Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy,31(3-4), 195-197. doi:10.1080/15360288.2017.1420120