A Review of Managing Less Common End-of-Life Symptoms

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

In the hospice setting, many healthcare practitioners are familiar with more common end-of-life symptoms. These include pain, constipation, nausea and/or vomiting, anxiety, agitation, or dyspnea. However, there are some less common symptoms that hospice patients may encounter, which may include hiccups, metallic (or bad) taste, and dizziness.

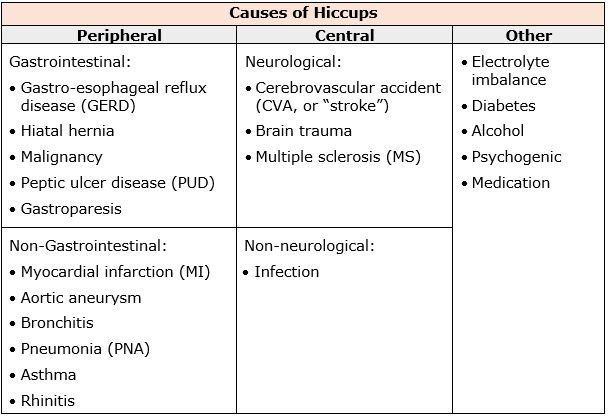

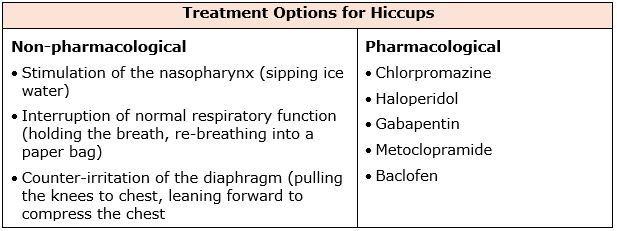

The definition of a hiccup is an involuntary spastic contraction of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles that leads to inspiration of air, followed by the abrupt closure of the vocal folds (Jeon et.al., 2018). Hiccups can be classified based on duration – hiccup bouts can last up to 48 hours, persistent hiccups anywhere from 48 hours to 1 month, and intractable hiccups that tend to last more than a month. Hiccups can be commonly experienced in any individual (adults, children, infants, and in utero).

The prevalence of hiccups is not well known. No racial, geographical, or socioeconomic variations have been noted. In general, the prevalence of hiccups is thought to be higher in children, men, and patients with comorbid conditions. Most hiccups are benign and self-limited, ceasing within hours. Data indicates that persistent and intractable hiccups can be extremely distressing and have a significant negative impact on quality of life for almost 1 in 10 palliative care patients.

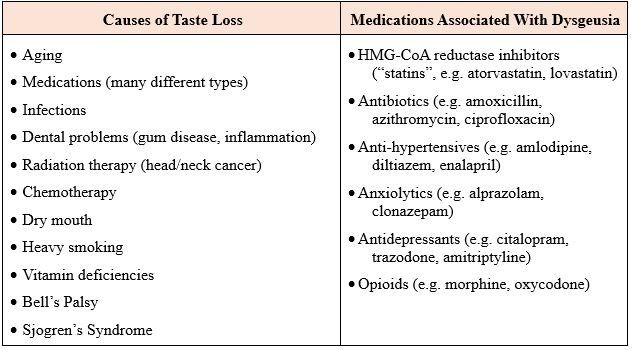

Another symptom hospice patients may experience is a type of taste disorder characterized by a persistent metallic, bitter, or salty taste in the mouth. This is called dysgeusia, which is a distortion of the sense of taste. It often occurs in older people, usually because of medications or oral health problems. It is the most common taste disorder.

Treatment options for dysgeusia include: the removal of the offending medication, if appropriate; use of sugar-free gum or hard candies (mint, lemon, or orange flavors suggested); rinsing mouth with a salt and baking soda solution before meals; or adding sweeteners like maple syrup or agave nectar to tame the taste issues.

Finally, dizziness is a term used to describe a range of sensations such as feeling faint, woozy, weak, or unsteady. Dizziness that creates the false sense that you or your surroundings are spinning or moving, is called vertigo. The feeling of spinning often starts suddenly, usually initiated by moving the head, and lasts anywhere from a few seconds to minutes. Risk factors include age and/or previous episodes of dizziness. Older adults are more likely to have medical conditions that cause dizziness, especially a sense of imbalance, and are more likely to use medications that can cause dizziness.

People experiencing dizziness may describe any of number of sensations, including a false sense of motion or spinning (vertigo), lightheadedness or feeling faint, unsteadiness or loss of balance, or a feeling of floating, wooziness, or heavy-headedness. Possible causes of dizziness from cancer and its treatment include medications (including, but not limited to, many types of chemotherapy), nausea and vomiting, or anemia. Other potential causes might include high blood pressure, hypoglycemia, dehydration, infection, or stroke.

Tips for coping with dizziness include drinking plenty of fluids, changing positions slowly, walking slowly and carefully, holding handrails up and down stairs, or using a walking device. Reviewing a patient’s medication list for drugs that might cause dizziness and are candidates for discontinuation, is another important strategy.

Our expert clinical pharmacist team remains available 24/7/365 to help identify potential causes of some of those tricky, less common end-of-life symptoms, and to help guide therapy selection (or de-prescribing if appropriate) to manage them. We are ready and eager to assist!

Written by: Jennifer Procaccino, PharmD

References:

1. Jeon YS, Kearney AM, Baker PG. Management of hiccups in palliative care patients. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2018; 8:1-6

2. Steger M, Schneemann M, Fox M. Systemic Review: the pathogenesis and pharmacological treatment of hiccups. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 1037-1050

3. Anneser J, Arenz V, Borasio G. Neurological Symptoms in Palliative Care Patients. Frontiers in Neurology April 2018; 9:275

4. Lexicomp Online. Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Hudson, OH. Available at: http://online.lexi.com. Accessed 10/2020.

5. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin URL: https://www.mypcnow.org. Accessed 10/2020.

6. Aging Care website. URL: https://www.agingcare.com/articles/loss-of-taste-in-the-elderly-135240.htm. Accessed 10/2020.

7. Cancer Net website. URL: www.cancer.net. Accessed 10/2020.