Managing Drug Interactions in the Hospice Patient

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

“Drug interaction” generally refers to an interaction between two or more drugs that alter the performance of at least one of the interacting drugs. Prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medications, nutritional supplements, herbal products, foods, diagnostic agents, and other chemical substances have the potential to participate in interactions. These interactions may alter medication absorption, distribution, metabolism, or elimination, which can, in turn, change their concentration, efficacy, or potential to cause adverse effects. Because drug interactions are so common, interactions are generally expressed in “levels of severity” to help identify the degree of risk.

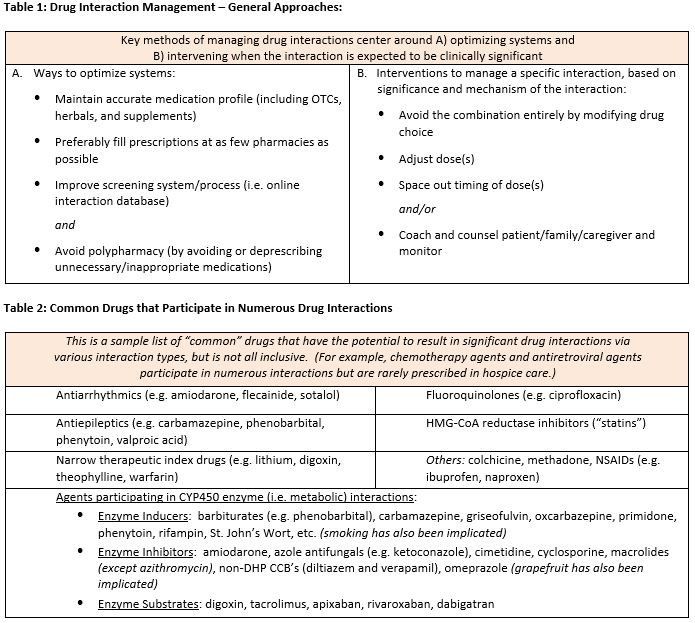

Even though some medications such as benzonatate (Tessalon Perles®) do not participate in any known drug interactions, the majority of medications do have the propensity to “interact” with other medications, as well as foods, beverages, substances, or even medical conditions. Significant interpatient variability exists, in that potential or expected drug interactions do not always result in an actual clinically significant outcome. Genetic variability, including enzymatic polymorphism, is believed to play a key role in creating this variability. The Medicare Hospice Conditions of Participation (CoPs) state that comprehensive assessments must take into consideration a patient’s drug profile, including actual or potential drug interactions. Thus, a case-by-case comprehensive medication review is recommended for each patient to assess the risks vs. benefits of a potential drug interaction.

Metabolic Interactions:

Metabolic drug interactions, which are primarily mediated by the Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes in the liver, are generally considered to be the most numerous and significant due to their ability to increase or decrease the concentration of certain medications. Upwards of 90% of drugs are metabolized in some way by these enzymes. Management of clinically significant metabolic drug interactions is typically achieved by reducing or increasing doses of an interacting medication depending on how it metabolically interacts. Dose changes might be required empirically (i.e. before the new interacting drug is administered), or it may be acceptable to adjust doses during therapy as needed, while closely monitoring the patient’s response. However, some interactions may not be clinically significant and may require no action outside of monitoring the patient. Other metabolic drug interactions are so significant that they should be avoided altogether.

Absorption Interactions:

Absorption interactions, whereby one or more drugs directly interfere with the absorption of another, are also common. However, absorption interactions may be more easily managed than metabolic interactions by simply separating the timing of doses — check with a pharmacist or refer to a reliable drug information resource for recommended separation times. A common example is the requirement to separate the administration of ciprofloxacin (or any antibiotic in the fluoroquinolone class) from fortified foods/drinks (e.g. yogurt) and/or minerals (e.g. multivitamin or certain antacids that contain calcium, aluminum or magnesium) by several hours.

Synergistic & Antagonistic Interactions:

Other common drug interactions in hospice and palliative care include synergistic (also known as “cumulative”) interactions, as well as antagonistic interactions. Common synergistic drug interactions include the serotonergic agents (where multiple drugs with serotonergic activity may result in serotonin syndrome), QT-prolonging agents (where multiple drugs which prolong the QT interval may result in Torsades de Pointes and/or sudden cardiac death), and anticholinergic agents (where multiple drugs with anticholinergic effects may result in anticholinergic syndrome). Other examples of synergistic groups include constipating agents, ototoxic agents, agents that increase bleeding risk, and CNS depressants. On the other hand, antagonistic interactions (where two or more drugs have opposing effects) are also common. An example of an antagonistic interaction is the combination of an antipsychotic such as haloperidol, which can worsen movement disorders, and carbidopa-levodopa, which is used to improve movement disorders. The risk of this interaction may be minimized by converting the offending antipsychotic to quetiapine (Seroquel®), which has less propensity to interact with movement disorder medications as compared to other antipsychotics. Another antagonistic interaction is the use of midodrine to prevent hypotension and orthostasis while taking a blood pressure medication, which can cause hypotension and orthostasis. Many hospice patients have low blood pressure and/or a relaxed requirement to control blood pressure. Thus, these blood pressure lowering medications might be stopped or tapered off, avoiding the need for midodrine.

In hospice care, certain drug interactions may be unavoidable or difficult to manage due to complex drug regimens and the desire to treat distressing symptoms. Polypharmacy can make it nearly impossible to predict the overall outcome of numerous interacting medications; thus deprescribing unnecessary and non-essential medications becomes a key management strategy for avoiding drug interactions. A case-by-case comprehensive medication review is recommended for each patient to assess the risks vs. benefits of a potential drug interaction and how to best manage it. To help identify and determine how to manage any clinically significant drug interactions, or for deprescribing recommendations, our clinical pharmacists are available to assist 24/7/365. We look forward to hearing from you!

Written by: Brett Gillis, Pharm.D., R.Ph

References:

1. Ansari J. Drug interaction and pharmacist. J Youn Pharm 2010;2(3):326-31.

2. Carpenter M, et al. Clinically relevant drug-drug interactions in primary care. Am Fam Physician 2019;99(9):558-64.

3. Medicare and Medicaid programs: hospice conditions of participation. 2008;73 FR 32087:32087-220.

4. State operations manual: appendix m 2020;200.

5. Falconi G, et al. Drug interactions in palliative care. NCBI 2020.

6. Farzam K, et al. QT prolonging drugs. NCBI 2020.

7. Horn, et al. How to address a drug interaction alert. Pharm Tim 2010.

8. Lexicomp: Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. https://online.lexi.com (accessed 2021).

9. Spanakis M, et al. Empowering patients to avoid clinical significant drug-herb interactions. Med 2019;6(26).

10. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. Anticholinergic syndrome. SCV

11. Volpi-Abadie J, et al. Serotonin syndrome. Ochs J 2013;13:533-40