The Management of Insomnia in Hospice Care

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

Insomnia is defined as difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, and/or having non-restorative sleep, and it is most often secondary to another cause or condition. Common causes of insomnia that can be especially common in the hospice population include the following: situational (e.g. interpersonal conflict/family dynamic issues); medical (e.g. cardiac, respiratory, pain, diabetes, GERD, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease); psychiatric (e.g. depression, anxiety); and pharmacologic (e.g. beta-blockers, diuretics, steroids, SSRI antidepressants). Whenever possible and as appropriate, it is recommended to treat and resolve the cause(s) of insomnia first, before adding a medication to treat the symptom of insomnia.

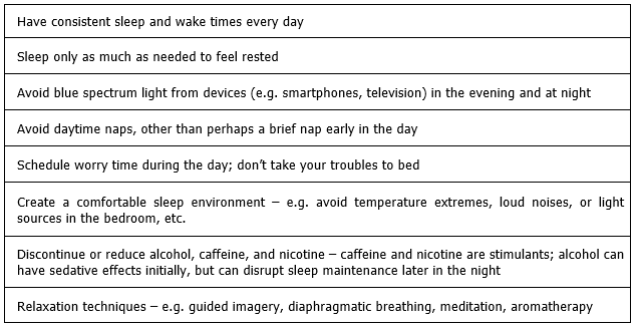

Non-pharmacologic measures should be used whenever possible to manage insomnia. In the hospice population, these might include:

Medication Therapies for Insomnia

There are a number of different types of medications that are used to treat insomnia:

Benzodiazepines

Temazepam (Restoril®) is FDA-approved for the treatment of insomnia, while lorazepam (Ativan®) is sometimes used off-label for the treatment of insomnia (typically for insomnia due to anxiety). Lorazepam and temazepam are among the benzodiazepines considered less risky for use in elderly patients.

Nonbenzodiazepine GABAA Agonists

These medications are also known as the “Z” drugs: zolpidem (Ambien®), zaleplon (Sonata®), eszopiclone (Lunesta®). The FDA recently added a Black Box Warning for these medications, because they have been associated with complex sleep behaviors that have resulted in serious injuries and death. These behaviors can occur after the first dose or after longer periods of use, even at the lowest recommended doses. The FDA also added a contraindication against use of these drugs in patients who have experienced an episode of complex sleep behavior in the past with their use. Due to safety, the max dose in the elderly and in female patients is 5mg per night.

Melatonin Receptor Agonist: ramelteon (Rozerem®)

Ramelteon works by binding to and stimulating the melatonin receptors in the central nervous system (CNS). Although this medication is reported to have minimal adverse effects and no withdrawal or rebound insomnia effects as compared to placebo, it is considered non-preferred in hospice due to its relatively high cost.

Orexin Antagonist: suvorexant (Belsomra®)

Suvorexant blocks the neuropeptides orexin A and B, which promote wakefulness. It also has minimal adverse effects and no withdrawal or rebound insomnia effects noted when discontinued, but it also tends to be relatively high cost and is therefore non-preferred in hospice.

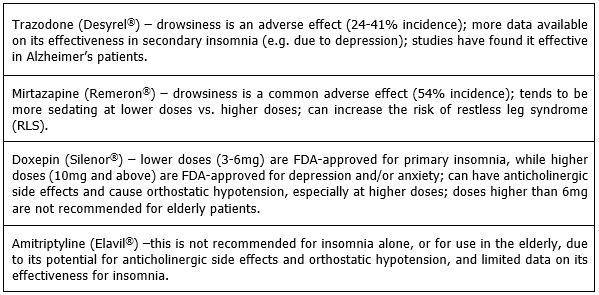

Antidepressants

These medications are typically (and likely most appropriately) used when the patient also has depression, or when other options have failed. Antidepressants can be sedating due to a variety of mechanisms, but they tend to lack data regarding their use in primary insomnia (with the exception of doxepin). The following antidepressants have support for off-label use for insomnia:

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics are not recommended for insomnia alone, but they can be effective for patients with insomnia AND behaviors/symptoms of psychosis, major depressive disorder, or an organic brain syndrome. Of the antipsychotics that are most commonly used in hospice, chlorpromazine (Thorazine®), olanzapine (Zyprexa®), and quetiapine (Seroquel®) tend to be the most sedating. Quetiapine is probably the most cost-effective.

Other Prescription Drugs: gabapentin (Neurontin®)

Typically, gabapentin should not be used for its sleep effects alone, although drowsiness is a somewhat common adverse effect. It may be helpful for patients with insomnia AND restless leg syndrome (RLS) or neuropathic pain.

Over-The-Counter (OTC) Sleep Aids

Antihistamines (e.g. diphenhydramine (Benadryl®), doxylamine) can have significant anticholinergic side effects, especially in elderly patients. Limited evidence exists on the safety and efficacy of use for insomnia. Note that tolerance to their sedative/sleep effects can develop with regular use.

Melatonin supplements mimic the function of the melatonin that our bodies produce, which is beneficial, as melatonin production and peak levels tend to decrease as we age. It is recommended to use the lowest possible dose (1-2mg in elderly patients, 3-5mg in non-elderly), as higher doses can cause supraphysiologic levels which can lead to desensitization. Controlled-release forms should be avoided in the elderly.

As a reminder, ProCare clinical pharmacists are available 24/7 to determine which sleep medications might be the most cost-effective and safe for your patients.

Written by: Joelle Potts, PharmD, BCG

References:

- Dopp JM, Phillips BG. Sleep-Wake Disorders. Chapter in: Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, 10th Edition; DiPiro JT, et al, Eds. McGraw-Hill Education, New York. 2017. 1111-22.

- Winter WC. The Sleep Solution: Why Your Sleep is Broken and How to Fix it. Berkley, Penguin Random House LLC, New York. 2017.

- Patel D, Steinberg J, Patel P. Insomnia in the elderly: A review. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine; June 15, 2018; 14(6): 1017-24.

- Schroeck JL, et al. Review of safety and efficacy of sleep medications in older adults. Clinical Therapeutics. Nov 2016; 38(11): 2340-2372.

- Kryger M, Kryger E. What every pharmacist should know about sleep. ASCP Webinars; UAN: 0203-0000-18-076-H01-P. November 3, 2018.

- PL Detail-Document, Comparison of Insomnia Treatments. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. July 2014. Last modified January 2015.

- Drug monographs. Lexicomp Online, Hudson, Ohio: Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information, Inc., © 2019; last accessed 6/25/2019.

- Brooks, Megan. FDA Adds Boxed Warning to Insomnia Drugs. Medscape. April 30, 2019.

- 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 00:1-21, 2019. Available at: [LINK] [last accessed 5/18/2019]

- Davis L. Melatonin: Shining some light on the hormone of darkness. ASCP Webinars; UAN: 0203-0000-18-022-H01-P. May 23, 2018.

- Natural Products Database, via Lexicomp Online, Hudson, Ohio: Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information, Inc., © 2019; last updated 4/19/2019. [accessed 5/15/2019]

READY TO START A CONVERSATION?

Request a Live Demo and Find Out How Your Organization can be ‘Powered by ProCare Rx’

All Rights Reserved | Burgess Information Systems