Use of Ketamine for Pain Management in Hospice Care

This document is for informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. All information contained in this document is protected by copyright and remains the property of ProCare HospiceCare. All rights reserved.

Ketamine shows promise as an effective option for hospice patients who have pain that does not fully respond to increasing doses of opioids. However, in all instances, this treatment option should be discussed and approved by the patient’s medical provider. It may be especially useful for neuropathic pain that does not respond fully to usual pain regimens that may include, opioids, NSAIDS, certain antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and gabapentinoids. Ketamine appears to be synergistic with opioids in patients who no longer have an analgesic response to high doses of opioids. It is also reported to be opioid-sparing and appears to play a role in opioid potentiation. Keep in mind the use of ketamine for pain is off-label and it can be very complex to dose, so coordination with the patient’s medical provide is critical.

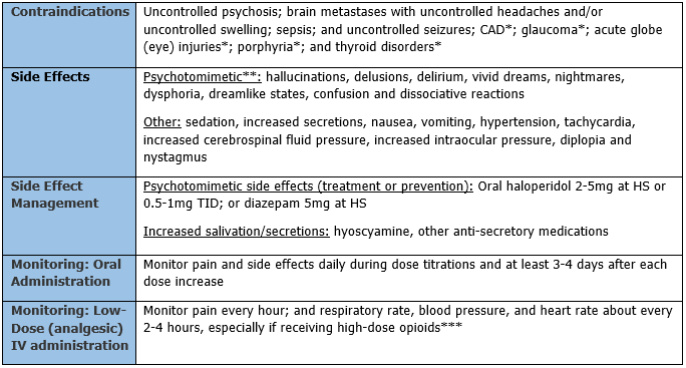

Contraindications, side effects, and monitoring parameters are listed in Table 1. If needed, a ProCare pharmacist can provide information to facilitate your decision about whether or not ketamine would be appropriate.

*Relative contraindications (may not apply to hospice patients). Evaluate risks vs. benefits of using in a hospice patient.

**Less likely with oral administration of ketamine than with infusions.

*** Ketamine does not suppress respiration, but can cause a reversal of opioid tolerance and opioid potentiation, which may suppress respiration if the opioid dose has not been reduced appropriately.

Ketamine is soluble in water and lipids and has many routes of administration. It can be given intravenous, subcutaneous, intramuscular, oral, sublingual, nasal, rectal, topical, and epidural. Dosing via the oral, sublingual, intravenous, and subcutaneous routes are most commonly used for pain and will be reviewed further.

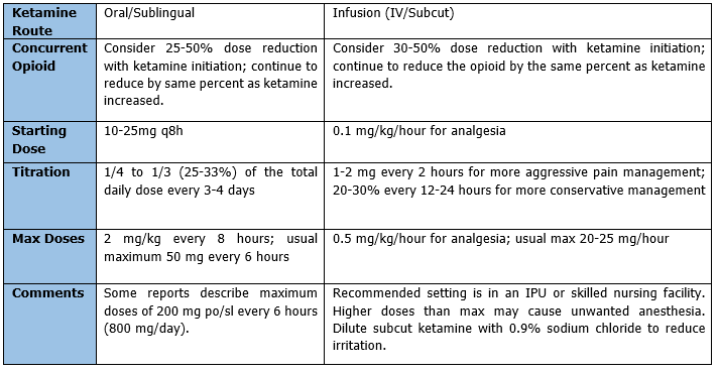

Ketamine dosing is complex. Concurrent opioid adjustments are generally also needed. Oral or sublingual administration of ketamine is preferred. Ketamine infusions can be used, but are best reserved in an inpatient setting, and should not exceed a specified max, in order to avoid anesthesia. See table 2.

When able, patients on continuous infusions of ketamine can be converted to oral ketamine. The conversion range is 1-3:1 IV:PO. If the patient has only been on the ketamine infusion for a few days, use a conversion range of 1:1. Give the total daily oral dose in three divided doses. Generally, a taper off infusion while starting oral medication is recommended. For the first 24 hours, continue parenteral ketamine at 50% or original rate. If possible, reduce parenteral ketamine to 25% of original rate on day 2 before stopping the infusion. Titrate the oral dose by 10-25 mg/day every 3-4 days or by 20-30% every 3-4 days. If the patient experiences pain before next dose is due, consider shortening the dosing interval.

In summary, the advantages, disadvantages, and possible contraindications must be evaluated to determine if the patient is a candidate for ketamine. Some advantages of ketamine include that it is a non-opioid for pain, has no significant effect on pulmonary function, has many routes of administration and is cost-effective when compared to most other pain regimens. Disadvantages may include possible psychotomimetic effects (though not as likely with oral dosing), little data regarding long-term use, it must be compounded for oral or sublingual use, kept refrigerated, and is only good for seven days. Although not a first-line agent for pain, ketamine may provide another good option for patients that fail to fully respond to increasing opioid doses and other adjuvants for pain management, provided the patient’s physician confirms the alternate treatment protocol.

Written by: Karen Bruestle-Wallace, Pharm D, BCGP

References:

- Li, L. and Vlidides, P. (2016). Ketamine: 50 Years of Modulating the Mind. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10(612), DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00612

- Ketamine. (2019, March 1). Retrieved from http://www.cesar.umd.edu/cesar/drugs/ketamine.asp

- Anderson, L. (2018, Nov. 5). Ketamine Abuse. Retrieved from https://www.drugs.com/illicit/ketamine.html

- Lexi-Comp OnlineTM, Lexi-Drugs Online TM, Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp, Inc.; Accessed: June 2018

- Ingraham, P. (2018, Nov 21). The 3 Basic Types of Pain Nociceptive, neuropathic and “other” (and then some more”. Retrieved from https://www.painscience.com/articles/pain-types.php

- ProCare HospiceCare, (2016). Ketamine Use-Quick Guide. (brochure). Gainesville, GA: ProCare HospiceCare.

- Clark, J. (1995). Effective Treatment of Severe Cancer Pain of the Head Using Low-Dose Ketamine in an Opioid-Tolerant Patient. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 10(4), 310-314.

- Rigo, F. K., Trevisan, G., Godoy, M., Rossato, M., Dalmolin, G., Silva, M.,…Ferreira, J. (2017). Management of Neuropathic Chronic

READY TO START A CONVERSATION?

Request a Live Demo and Find Out How Your Organization can be ‘Powered by ProCare Rx’

All Rights Reserved | Burgess Information Systems